Burn Lin knows the ins and outs of the tiny chips that power your phones, cars and gaming consoles, and he knows there aren’t enough workers to keep up with skyrocketing demand.

The electrical engineer started his career at IBM in 1970, but eventually returned to his roots in Taiwan where his work helped turn the island democracy into the chip-making capital of the world. He led technological breakthroughs at Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., today the crown jewel of Taiwan’s tech industry.

Now he’s been tasked with preparing the next generation of leaders for a murkier, more arduous future in the technology that makes much of modern life possible.

The world of semiconductors has changed since the former Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. vice president left the business. A severe pandemic-induced chip shortage laid bare the breaking points of a complex global supply chain. Rising geopolitical tensions have sown mistrust and prompted countries to pour money into chip-making facilities of their own.

Burn Lin led technological breakthroughs at Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., today the crown jewel of Taiwan’s tech industry. Burn Lin accepts the Presidential Innovation award.

(Burn Lin)

Meanwhile, artificial intelligence is boosting demand for more efficient microchips. But semiconductor engineers are running up against the physical limits of Moore’s Law, a long-held projection that the number of transistors on an integrated circuit will double every two years, making them smaller and faster.

The number of workers required to design, manufacture, test and package all these chips will be enormous. According to consulting and financial services giant Deloitte, semiconductor companies will need an additional 1 million skilled workers or more by 2030.

Lin, now dean of the College of Semiconductor Research at Taiwan’s Tsinghua University, knows he won’t be able to fill that gap. His school — created with government support three years ago to address the growing talent shortage — trains about 100 students every year, far short of the 10,000-some additional workers needed annually in Taiwan alone. But he hopes those few will become leaders that keep Taiwanese companies ahead.

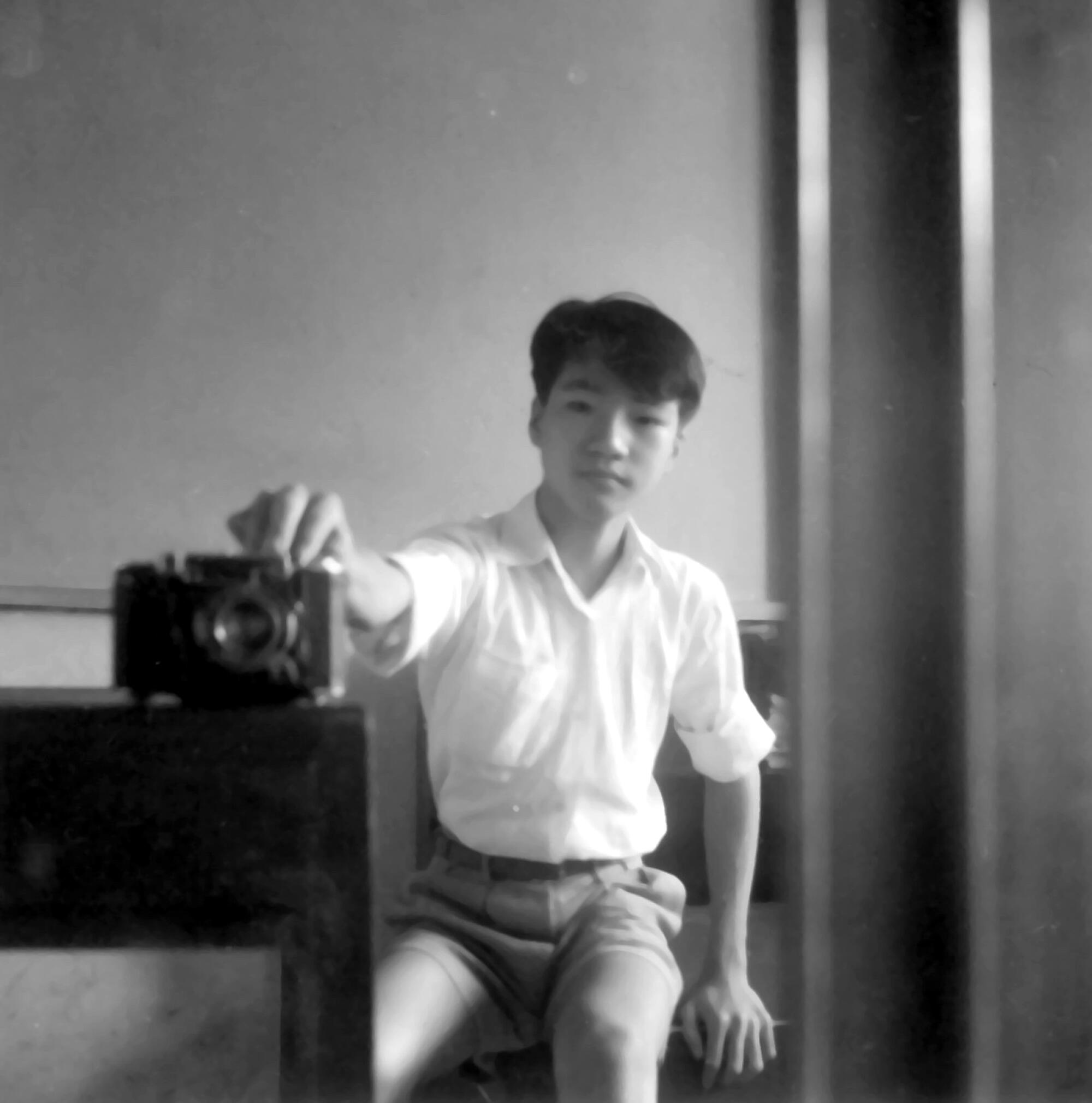

Burn Lin takes a selfie as a youth.

(Burn Lin)

For an island facing threats of military assault from China — which claims the island as part of its territory — a competitive edge in inimitable technology is even more critical. Taiwan manufactures one-fifth of the world’s chips and 69% of its most advanced ones. That dominance has become known as Taiwan’s “silicon shield,” since nations that rely on Taiwanese chips have incentive to help protect it.

The Times spoke with Lin about his efforts to keep Taiwanese talent ahead as the race for self-reliance in chips heats up, and how that competition is changing the industry. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How will the semiconductor worker shortage impact the industry? Does that mean some countries fall behind?

Countries have become more selfish, so to speak. They only worry about their own benefit, and forget that the semiconductor industry needs a lot of collaboration to grow.

There are some countries good at making equipment: for example, the U.S., Japan and Germany. There are some countries that are very good at design, very innovative. The U.S. is also a big contributor in that area. And then there are countries that are good in manufacturing. Even in the U.S., there’s Intel and Micron. And people think that our TSMC is very powerful, but if we don’t get all the materials and equipment, we stop operating in a few weeks.

The logo of TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co.) during the Taiwan Innotech Expo at the World Trade Center in Taipei, Taiwan, in 2022. Taiwan is reducing its reliance on the Chinese mainland as it seeks to insulate itself from pressure from Beijing while forging closer economic and trade ties with the United States.

(Chiang Ying-ying / Associated Press)

So if there are four countries that would like to be independent, then it just thins down the process and makes the efforts very uneconomical. You have to do four times the research instead, with many duplicating each other’s work.

Does that mean that accepting interdependence would alleviate the worker shortage?

Yeah, that would greatly alleviate that. For U.S. students, most of them want to go into design, if they go into semiconductors at all. So where do you find the other people for other disciplines?

Is the shortage because demand is growing or there are fewer people interested in this field?

Both.

The need for more advanced chips is very high. And there are a lot of other fields for people to choose from. Even in Taiwan, people used to pick semiconductors as one of their top choices. But now they have their eyes on so many other areas, like the financial sector, medicine, biological science, politics and so forth.

I think in the U.S. or Japan, the situation is worse, because those people have even more choices. They would rather go to work for Apple or Google, instead of going to work for [a chipmaker like] Intel. Intel used to be very attractive employer. That’s no longer the case.

Most new students want to study design instead of the manufacturing process. That’s the worldwide trend. We’re no exception here. People view sitting there as much easier, right? They don’t have to dress up for the clean rooms [where semiconductors are made]. They can just move their fingers instead of moving their feet.

Burn Lin photographed with his family.

(Burn Lin)

There’s also this kind of social influence. The internet is so easy to reach, and pretty soon you find that all the students are contaminated. They are all connected to the web, and everyone thinks that, oh it’s much better to work sitting at a desk instead of working in a clean room. A lot of people are moving toward an easier life.

We have to make life more pleasant for people. Taiwanese companies, for example, you find gyms in there, cafeterias, good food and recreational equipment. So they are trying to make the workplace appealing.

What’s been the biggest change since you were working in the private sector?

When I was working in the U.S. and in Taiwan, we spent a lot of time and effort to shrink the circuits from one generation to next.

Moore’s Law of scaling has slowed, or I would even say stopped. The shrinking has to stop because we’re reaching the atomic level. But if we use the spirit of Moore’s Law, the spirit is that the technology will move on. If you rearrange the chip in a better way to use memory, you can make it work faster with less energy, but without changing the size.

Sometimes it’s easier, sometimes it’s not. Over the last few decades, we have become very lazy in innovating, because we thought, “If I can just scale it down, I can make it more attractive. Why bother to think about new things?”

The university then plays a very important role, because they can afford to look at new, high-risk things that you have to spend a lot of time studying to make sure are reliable and suitable for large-scale manufacturing. Right now, quantum computing is still at a very early stage, and people going into it are taking a very high risk. But we should still do that.

Workers gather for a ceremony that marks the beginning of bulk production of advanced 3-nanometer chips at a Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. facility in Tainan, Taiwan, in December 2022.

(Lam Yik Fei/Getty Images)

Why did your college add a course for engineering students on geopolitics?

In addition to just making better chips, we now have to satisfy the policymakers and the people who control the money.

Learning about it doesn’t mean they have to become an expert. The industry has to hire some geopolitical experts or economic experts to guide them and negotiate or lobby for them. But for students, they have to be exposed to all kinds of possibilities.

For example, if the customer is a government, then you have to know what they are thinking and what they need in addition to the technology. If your customer is in a foreign country, then you have to worry about whether you can sustain the relationship or whether there will be other political forces that break it.

Has it become harder to work in the semiconductor industry compared with 20 to 30 years ago?

A: Yeah, it’s harder. But it’s more fun. It’s less routine. It’s a growing industry. So people see the potential in it.

Follow www.latimes.com , phenofornia Team Editor